when you want, where you want.

What Is Zabar’s Without Saul?

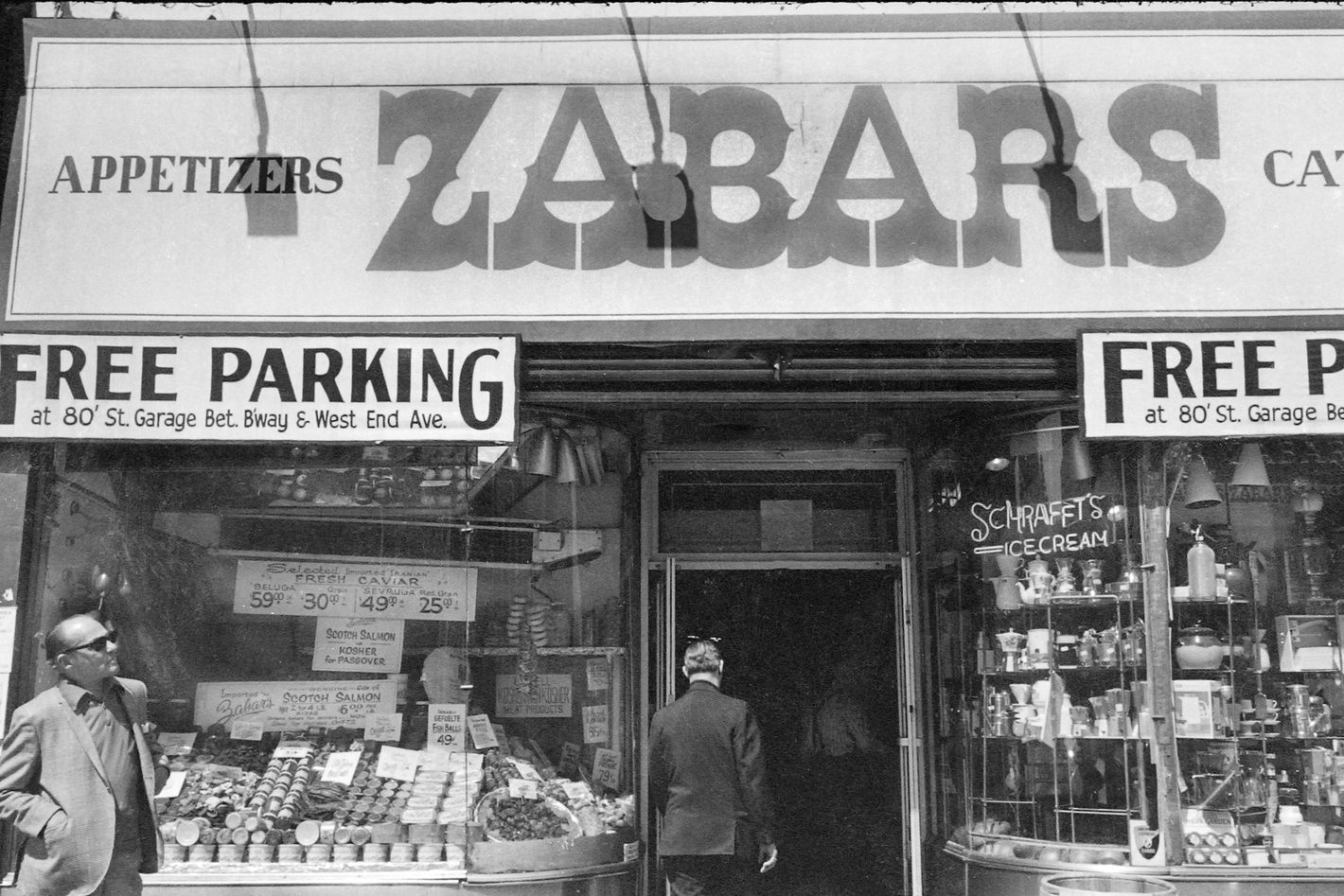

Photo: Michael Gold/Getty Images

Photo: Michael Gold/Getty Images

On more than one occasion, I had heard people mistakenly refer to Saul Zabar as the founder of his family’s famous Upper West Side store. I understood the confusion: Saul, who died this week at the age of 97, was old enough to have been around when his parents, Louis and Lillian, opened shop in 1934. Although he’s one of three Zabar brothers — middle brother Stanley has always been more behind the scenes; Eli, the youngest, broke out on his own decades ago on the east side of the park — Saul was the institution within a landmark.

Even members of the Zabar clan looked at him with a certain reverence. “I always kind of saw Saul as this sort of legendary being. When I was young, I was in awe of him,” his great-nephew Willie Zabar says.

Rachel Zabar, Saul’s daughter, remembers visiting the store as a child and waiting for her father to leave so the family could go to dinner: “I remember so vividly how it was impossible to get him to leave.” But she says she’s grown to understand what motivated him. “Perfectionist is not a strong enough word,” she explains. “It’s an unflappable sense of right versus wrong, integrity, and honesty — my dad did what he did and was how he was because that was the only way to do the job: Give the customers the most perfect product because he knew what that was and it was achievable.”

Guys like Saul were the norm in establishments opened by Eastern European Jews who likely came to New York to escape the cruelties of czarist Russia, as his own parents had. He came from the same school of hospitality as guys who worked at the 2nd Ave. Deli when it was actually on that street and anyplace else a customer would get cursed out in Yiddish if they took too long with their order. They cared so much about what they did that they simultaneously gave no fucks about anything else. That was especially apparent in the way Saul sampled all the things that Zabar’s made and sold.

“You didn’t want to get between him and his latke tasting,” Willie says. Saul, famously and not unlike a wine sommelier, spit out everything he tried. That includes potato pancakes around Hanukkah: “I remember standing behind the deli counter one day while Saul was sampling the latkes, and an employee kind of gently but firmly moving me out of the way so that Saul could spit the latke into the bucket.”

Anybody who has spent more than a few afternoons browsing the aisles of the shop on Broadway probably saw Saul standing behind the fish counter or examining the Brie — almost always in his white deli coat with the store logo sewn onto it — and possibly heard him or at least considered he was a guy who had no problems saying fuck in public. He was, in the kindest, most perfectly New York way possible, a crank, the sort of person who seemed perpetually annoyed and short of time for schmucks, but who locals knew by first name and (almost) always had nothing but nice things to say about.

Photo: Michael Gold/Getty Images

Photo: Michael Gold/Getty Images

“These foods and these physical spaces have become seared into people’s memories as their important life events,” says Niki Russ Federman, the fourth-generation co-owner of her family’s Lower East Side shop, Russ & Daughters. “Saul was a reflection of that. He was always there. Even as a kid, when my father would take me to the fish smokehouse, I would see Saul there. It was that generation of work ethic, of being physically there, of checking every fish, of having somewhat maniacal oversight and the commitment to just being there to do the work and make sure things went well.”

Symbolically, Saul’s passing feels like the real end of something. There was talk about retiring in the 1970s, and as Rachel points out, “He had a period in maybe the ’80s when I believe he was not running the store — more a tasting and buying role.” But he “went full-time in overdrive” after one of his partners, Murray Klein, retired from the business. Saul had always acted as the store’s de facto spokesperson, “but he always said it’s not about one person.” Willie learned this lesson when he started a podcast dedicated to the people and stories that make the store what it is. “There was a poster in the front of the store that featured me in my deli slicer jacket with a microphone, and it disappeared,” Willie says. “I was told it was because Saul was not happy about it” — nothing in the store is about one person, after all — “and, I can’t confirm this since I didn’t see with my own eyes, but I choose to believe that Saul personally ripped it down with his bare hands.”

I got a firm “no comment” when I asked who served as the store’s figurehead these days. It’s fun to think of some Succession With Smoked Fish drama unfolding now that the reigning patriarch is gone, but everyone is quick to dispel the idea that infighting will be the cause of the store’s demise. Other, similar businesses have weathered similar disruptions: Joel Russ, for example, could never have imagined the success his daughters and now grandchildren would have with the little Lower East Side storefront where he sold pickled herring back in 1914. The Zabars have kept things almost entirely within the family. The one most notable instance of when they allowed an outsider in was when former stock boy Klein was brought on as a partner; the relationship was filled with behind-the-scenes tension until Klein sued the family claiming he didn’t get what he was owed upon retiring. What more could an outsider do for Zabar’s besides buy it outright and make members of the family even wealthier than they are today? Russ Federman points out something her own father used to say: “No one’s going to care as much as the person whose name is over the door.”

I was wondering about any potential family infighting a few years ago when I sat down to dinner with Eli at his restaurant on the Upper East Side, a part of town he joked was his own “shtetl” away from the one his family had built to the west. Despite years of the media portraying Eli’s separation as a rift that could never be repaired, he spoke warmly of his brothers and their families. Willie also debunks years of media claims that there was any sort of bad blood between the brothers: “I can only speak to what I’ve seen with my own two eyes, but I’ll say this: Every year that I’ve been on this planet, Saul hosted the break fast for Yom Kippur; my grandfather Stanley hosts Hanukkah; and Eli does Passover every year, and they would all be there. No matter what, they’d end up sitting together; it was really adorable to see how much they loved one another.”

With all the tributes rolling in, it feels like Saul Zabar’s belief that the family store wasn’t just about one person is currently being tested. Certainly, members of the family understand what’s been lost, but they also think there’s something bigger to be protected than merchandise or sales. Willie Zabar sees Saul giving up his dream of practicing medicine in order to run the family business as “a sacrifice and an act of service.” He points out that back in 1949, Saul “wasn’t taking over this big storefront business with a mail-order operation and this huge brand — he was taking over a local business, and there was no guarantee of success.”

Related

All Rights Reserved. Copyright , Central Coast Communications, Inc.