when you want, where you want.

CJ Television

Drinking Wasn’t a Perk of the Job. Drinking Was the Job.

Photo: ZUMA Press, Inc. / Alamy Stock Photo/Alamy Stock Photo

Photo: ZUMA Press, Inc. / Alamy Stock Photo/Alamy Stock Photo

On a chilly November morning in 2001, a day off from work, I walked to Cibao Deli, on the corner of Avenue B and East 4th Street for a self-serve coffee. The man behind the counter had his radio tuned to 1010 WINS, the AM news station.

As I passed my dollar across the counter, I heard the radio announcer say that an American Airlines plane bound for the Dominican Republic had crashed a short time ago in Queens, minutes after taking off from JFK, and that all 260 passengers and crew, plus a dog, were presumed dead. The bridges and tunnels were closed, all the New York City airports shut down.

It had been two months since 9/11, and parts of downtown still smelled like a tire fire. You’d occasionally see people wearing gas masks on the street or selling American-flag-printed T-shirts with terrible slogans like I SURVIVE [sic] THE ATTACK or SEPTEMBER 11, 2001: I CAN’T BELIEVE I GOT OUT. Most days, a wiry white man stood directly under the arch in Washington Square Park, yelling about how the hijacked planes had been chartered by Steven Spielberg, Mariah Carey, and the New York Mets.

We would learn within a few days that the crash had been a tragic accident, not a terror attack. The plane had wobbled after takeoff, the inexperienced co-pilot badly overcorrected, the vertical stabilizer came dislodged, and the plane fell out of the sky and into peoples’ yards and houses, instantly exploding in a fireball. Later investigations would show a design flaw in the rudder.

It was the second-deadliest aviation disaster in U.S. history, and yet because it was an accident, there was, in the atmosphere, a weird collective sense of relief about the whole thing, and a doubling down on the notion that “life is short” and “anything can happen,” which caused people to act in unpredictable ways, running full-speed toward, or swiftly away from, danger and uncertainty. Among people I knew, there were sudden breakups and ill-advised marriages. If I hadn’t already decided to quit my job as Mario Batali’s assistant, I would have done it then.

He’d offered me the job two and a half years earlier, for an annual salary of $26,500, with health insurance after six months. It never occurred to me to negotiate for even a dollar more. I was so relieved, so thrilled. He would later tell me that I was the only person who’d applied for the job. I had been at the right place at the right time; I’d get to work on a cookbook, and get right up next to the magnetic heat and excitement of the restaurant business, while avoiding the risk and damage inherent to the endeavor. On my first day, within 30 minutes, he’d given me the nickname Woolie.

The day after the plane crash, I was back at work, editing recipes at Babbo’s bar. Across the room, I could hear Durim, the new service manager, talking to a young phone girl.

“What did I tell you about blondes wearing pink?” he said, playacting at scolding her. “I can hardly control myself around you!”

The girl, an NYU freshman, smiled up at Durim from the banquette where she was seated, taking call after call. Her face was sheepish, her laugh light. She was wearing a blush-colored oxford shirt that was buttoned to the top of her sternum.

Durim had been on the job for about six months. When he first started, I wondered if he was too polite and softspoken for the loose, fun, dirty-talking culture of the restaurant staff. The busboys made fun of his Albanian accent, a combination of Italian and Slavic with a bit of the Bronx, and the waiters pushed back against his stiff notions of fine-dining service, which he’d honed in various four-star dining rooms. Durim must have spent some time quietly observing the prevailing horny ethos, because now here he was, pretending to be upset with a young employee because he found her fuckability a distraction.

It wasn’t just Durim: Mario’s vocal horniness had set a tone for everyone who worked at Babbo. His grabby hands and constant dirty jokes and innuendo signified that it was okay, even encouraged, to flirt with and grope each other. No one called it harassment, except perhaps when making jokes about it. I had a stack of publicity photos of Mario in a two-handed finger gun pose, a slight smile on his face. One morning before he came in, I took one from the stack and used a Sharpie to write the words “Free breast exams!” on it. I showed some female co-workers, to get a laugh. Then I put the photo in my bag and took it home, to be safe.

It was an open secret that Mario pawed at the women on staff.

One afternoon during setup, I’d seen him reach for the cotton drawstring that dangled down the front of a pair of lavender sweatpants worn by a cute young backwaiter named Ariela. His knuckles grazed her crotch for a split second before he pulled her toward him, using the string. She jumped back and shrieked, in the showily playful way of an adolescent girl being teased by an adolescent boy. Was she acting, to keep the peace? I had no way of knowing.

Within my first few months of working for him, Mario, ostensibly sober, also groped me during the workday, while I was taking a call on the cordless phone, walking in a kind of aimless circle around the dining room.

There were a few people around — a porter hauling laundry bags down the staircase, a telephone girl, one or two waiters starting to take chairs down from atop tables. No one was paying any attention when Mario beelined toward me, from the front door of the restaurant to the middle of the dining room. While I had my back to him, he simply grabbed my ass with one hand, squeezed hard, let go, and moved on into the kitchen.

I was rattled and distracted, but ended the call, and found Mario in the kitchen, leafing through invoices on a clipboard. I went and stood at his elbow.

“Hey. Please don’t do that again,” I said, quietly. I could see that I had startled him, but he instantly regrouped to furrowed-brow, narrow-eyed, curled-lip contempt.

“What are you, a lesbian?”

I laughed, then left the kitchen and went down to the basement to cry. It’s not really a big deal, I told myself then, and I think it now, as I write this. It wasn’t that big a deal. I told Jessica and my sister that Mario had grabbed my ass but didn’t discuss it with anyone at work. I didn’t want it to get back to him as gossip, and I didn’t want to burden anyone else with the knowledge.

Everyone had good reasons for wanting to be and stay at Babbo, which meant excusing the odd grope or weird innuendo. The front-of-house staff made great money, the cooks got the experience and the glory of working in a red-hot place with a red-hot chef, and even the phone girls and hostesses had access to the powers of saying “yes” and “no” to reservation requests.

Mario’s generosity with connections and opportunities was what kept me on the hook. As promised, he’d introduced me to food and travel editors, for whom I was now writing my own freelance stories. Mario had shared bylines with me in Paper and the Los Angeles Times and Wine Enthusiast. He sent me to continuing-ed classes in recipe writing, Italian, and HTML and trusted me with a lot of responsibility for his books and the recipes and guest bookings for his TV show.

And he threw me some substantial crumbs from his heaving table: tickets to a Saturday Night Live broadcast, a Willie Nelson concert, a Rangers game. A third-row seat at the celebrity-packed GQ Men of the Year Awards. Three more boozy, gluttonous working trips to Atlantic City, two to Aspen, and one each to Miami, Boston, Philadelphia. Endless free drinks and meals, and the occasional bottle of precious aceto balsamico. A Tiffany crystal football etched with the NFL logo. And his old laptop, in lieu of a cash Christmas bonus. (That one kind of sucked, actually.)

Mario could be tyrannical, irrational, and mean. I tried to move cautiously through each day to avoid triggering a flare-up of rage or the spark of a sudden vendetta. He put a lock on the restaurant’s stereo cabinet, which prevented anyone from interfering with his carefully chosen music selections. When he discovered that I’d unlocked the cabinet so that a manager could remove a CD that had been skipping during service, he called me a “pathetic moron,” told me I ought to remember whose team I was on, and hissed, “Have I not made it very clear that no one touches the music? It is my restaurant and I control the music.”

Later that day he tossed a bouquet of white roses and lilies onto my desk and said, “Sorry.”

He was forever on the defensive, paranoid that anyone else might be getting something more or better, and apoplectic if it turned out to be true. After one of our Atlantic City casino events, featuring several chefs, he was super-pissed to discover that the hotel had provided round-trip helicopter service from New York for Daniel Boulud and his team, while we’d only been offered a limousine. “Next time, Woolie, you demand me a fucking chopper.”

Deflecting his intrusions and absorbing his rage was the price of admission to a pool I nonetheless felt very fortunate to swim in. I had jumped into the water, and I knew it was wet. If I suddenly realized that I couldn’t swim, I thought, it was on me to find the ladder and climb out. I was one of dozens of women in his orbit who would laugh off his suffocating hugs and suggestive comments, the occasional tongue in the ear, the lacerating, humiliating verbal kicks in the back. We were too dependent on our jobs, too invested in maintaining a friendly atmosphere, to ever raise an objection, and anyway, wasn’t it just the nature of the rough-and-tumble restaurant business we all loved? Would things really be any different anyplace else?

When I decided to give notice, I didn’t consciously think, and never said, that it was because of Mario’s behavior. I believed it was because, as a generalist assistant in a world of specific competencies, I had learned all I would probably learn. I had been treading water, neither front of house nor back, and inessential to Mario’s burgeoning TV and writing careers. Six months out from publishing The Babbo Cookbook, he’d decided that my name would not go on the cover after all. It was close to the bottom of a long list of acknowledgments.

Also? I had drunkenly slept with too many co-workers, and now I wanted to meet someone nice, someone whose heart hadn’t been corroded by restaurant life. I was always broke, and I was drinking a lot, all the time.

Did I drink so much because I was unfulfilled, or was I unfulfilled because I drank so much? I had no idea. Everyone I hung out with, my colleagues and my college friends, drank and drugged; to relax, for fun, for the management of moods. I never said “no” to a bump of coke, and never ran out of weed, which I now had delivered to me at the restaurant.

Given the paramountcy of loyalty in Mario’s world, I was extremely nervous about leaving. Defectors were dead to him, for the sin of taking what they’d learned in his employ and applying it to someone else’s success. It wasn’t just Mario, of course; no one is happy when a valued, well-trained employee leaves, but Mario was ready to scorch earth over a hasty exit. I gave him 12 months’ notice, which was absurd, but I hoped it would protect me from being blacklisted if I ended up working for another chef or restaurant. It only occurred to me later that I’d also protected myself from a raise or bonus.

Close to the end of my lame-duck year as Mario’s assistant, we went to Melbourne, Australia, for that city’s Food & Wine Festival. Major sponsor Singapore Airlines gave us two business-class tickets, but Mario insisted on bringing two assistants, me and chef Mark Ladner, who at the time was running the Roman trattoria Lupa. I only managed to squeeze the airline for an extra coach-class ticket, so Mark and I would have to trade off sitting in business class with Mario, and alone in coach, over the course of our three flights to Melbourne.

We flew from Newark to Amsterdam on a Monday evening. I started in business class. I’d brought some Vicodin and Percocet that had been gifted to me by one of the phone girls with a side gig selling pills, and some Ativan that my primary-care doctor, a huge Mario fan, had prescribed for my (fictional) anxiety about flying. I took the drugs interchangeably, one of something every few hours, washed down with white wine. Mario drank one beer and fell asleep shortly after takeoff. The pills made me feel dumb and dissociated but were no match for Mario’s snoring. I did not sleep.

Despite a burgeoning head cold, I found the will to smoke three consecutive cigarettes in the smokers’ lounge, which was a few folding chairs arranged inside a grim, glass-walled box. I took an Ativan, then boarded the flight to Singapore, and for the next 12 hours, I had a few infrequent and jagged ten-minute increments of sleep, dreaming I’d been left in charge of a wolflike dog that I’d neglected to feed.

We had a five-hour layover in Singapore. Everyone was punchy. I’d lost track of the time of day, and the day itself. Mark and Mario and I drank big beers and ate bowls of steamy yellow noodles with pork and shrimp. I paid $20 to take a shower and $10 to sit in a recliner with a thin tube strapped to my face, inhaling purified oxygen. I took a Vicodin.

Back with Mario in business class for the final leg, I fell gratefully into my window seat, determined to sleep through the snoring this time. When the flight attendant offered him a drink, he said, “The lady and I will each have a Singapore sling.”

The cool red cocktail went down like cherry Robitussin on ice and then I had to pee. Mario set his empty glass down on his tray and depressed the seat-side buttons to elevate his legs and lower his head and shoulders.

“You know what, I actually need to get up and use the lav,” I said, just as he got fully reclined.

“I guess you’re gonna have to straddle me,” he said. I laughed. He didn’t.

“Woolie, I have already made myself comfortable,” he said. His voice had that high, tight tone of dangerous annoyance. “I know you’re not asking me to adjust my seat because you forgot to pee. You want to get up? Climb on up and over, baby.”

I was wearing a denim skirt that hit just above my knees, and I had to hike it up to scramble awkwardly across Mario’s lap. I faced him, so as to not expose him to my actual ass, but I kept my eyes on the carpeted aisle. He reached up and put his hands on my hips as I moved across him, and again when I did the same crawl back into my seat. I wondered how I might have avoided this humiliation. I could have worn an adult diaper, I guess, or refused to go on the trip. I closed my eyes and did not get up again.

We landed in Melbourne and it was, incredibly, Wednesday evening. The festival director, Sandra, met us outside the customs hall with a driver in a slim suit, who loaded our bags into a Mercedes van. Sandra was a handsome silver-haired woman in a navy shift and pearls, a slash of coral lipstick, and a cheer in her voice that shredded my nerves.

We went straight to dinner at Flower Drum, a fancy Cantonese restaurant, where we joined a huge round table of a dozen or so other festival presenters. Sandra directed me to sit next to an elderly American man named Hank. His wife was a cookbook author who’d be speaking and doing cooking demos.

“Do y’all experience asparagus pee?” Hank asked the group as I pulled my chair closer to the table. He was a retired chemical engineer and had some unique insights on the topic.

I was wrecked with fatigue, my throat and head pounding, my nasal passages now a fountain of thin yellow mucous. I chugged two quick glasses of Champagne and took a sip of water before the waiters began delivering the food: glistening, translucent spring-onion cakes, followed by scallops with lily buds and a whole roast sucking pig the size of a well-fed toddler, the meat tender, the skin like crunchy taffy. There was Murray cod fried in a rice-flour batter and garnished with soy sauce, scallions, and cilantro, then thin slices of abalone that had been cooked for 13 hours at low temperature, served with dainty baby bok choy. When the waiters retreated, Sandra told us that abalone retailed for $450 per kilo. Mario and Mark, seated across the table from me, both seemed somehow completely fucking functional, even chipper, whereas I was a mute shadow of a ghoul.

A waiter returned to let us know that there would soon be a duck course and a beef course, and that the chef and his cooks would then come out to introduce themselves before two dessert courses, which would be followed by coffee and brandy.

I was there to be a punching bag, a co-conspirator, a wingman, a straight man, a convenient female body …

I did the math on how much longer we would have to sit at this table, then heard the sound of shattering glass from somewhere inside my mind. I started to cry, silently, feeling not so much sad as held hostage. I closed my eyes, started to nod off, and when I opened them again, I saw that Mario was staring across the table at me with narrow-eyed fury. Sandra was up from her seat, coming around toward me.

“Come on dear, let’s leave the table,” she said, grasping my elbow, leading me to a bench near the coat check. I sat down. Mario had followed us; he sat next to me. Sandra smiled tightly and retreated.

“Get a grip, Woolie,” he hissed. “It’s gonna be a long fucking week if you can’t keep your shit together.”

“I’m sorry,” I mumbled, mashing my fingers across the tears on my cheeks. “I’m jet-lagged, I have a bad cold—”

“You’ve been taking some heavy fucking pharmaceuticals and drinking for two days,” he interrupted. “You can’t handle that shit. What did you think was gonna happen? Go splash some water on your face and come back to the table.” He got up and walked away.

I felt ashamed and furious, yet weirdly cared for, like Meadow Soprano being dressed down by her father, Tony. That the pills were a bad idea had never occurred to me. I took a few deep breaths, dug my nails into my palms, and went back to the table for the Peking duck, beef filet, milk-and-ginger pudding, and bird nest with almond soup. When the chef came from the kitchen to greet our table, he spoke only with Mario.

The next morning, soaking in a hot bath at the Park Hyatt, I coughed up green phlegm speckled with blood, like some clunky plot device foreshadowing my consumptive death, which I hoped would happen, so that Mario would feel suitably bad about scolding me.

Later, Sandra took us on a tour of the Queen Victoria Market, where for the first time I saw whole goats and lambs and kangaroos skinned and posed for display at a butcher’s stall. The animals’ intact eyes looked enormous in their bony faces. We ate sausage sandwiches and drank red wine for lunch, standing up in a corner, then went back to the hotel to prep for the first of Mario’s three cooking seminars.

He talked to the capacity crowd in his usual intense and authoritative cadence about the “miraculous and celestial love story between this specific pasta and sauce,” disparaged grocery-store butchers, and hinted that whisking zabaglione was just like jerking off, while Mark and I worked furiously backstage, plating small portions of bucatini all’amatriciana in a hotel production kitchen down a long hall from the ballroom.

For the next four days, between seminars and panel discussions, we were obligated to a full schedule of boozy long lunches and dinners with sponsors, the other festival presenters, and their spouses. We ate and drank some extraordinary things: unfamiliar game birds and black truffles and huge prawns and tiny vegetables, Persian fairy floss and fair-trade chocolate, Australian Shiraz and vintage Champagne and well-aged Sauternes and some very rare and exclusive sake. I kept a close watch on the room, and after each dinner, once I gleaned that it was even slightly not rude to do so, I retreated to the hotel, while Mario and Mark continued on into the night, drinking and smoking and making new friends.

On the morning of our last seminar, Mark said, “You know, the big man is really pissed at you for not going out drinking with us. He said you’re not being a team player, that you don’t have his back.”

I felt like throwing up. “Yeah, but I think I have, like, a sinus infection,” I said.

“I don’t know, maybe take some cold medicine and go out with us tonight,” Mark said. “I’m just the messenger.”

I’d failed to realize that being a drinking buddy wasn’t a fun perk of the job; it was the job. On paper, I was there to help tong pasta onto plates and hold on to business cards, but really, I was there to be a punching bag, a co-conspirator, a wingman, a straight man, a convenient female body, whether or not I had a cold or jet lag or just simply wanted some time to myself.

What did I expect? For three years, I was a good-time assistant, taking the trips and drinking the booze and laughing at the awful jokes and sometimes making them, too. My mistake had been believing that it was always my privilege and my choice to hang out with Mario and keep him company while he drank.

I couldn’t wait to be done with the job. I let Mark take the business-class seats all the way back from Melbourne to New York.

A few days after we got back from Australia, Mario handed me a Babbo business card, on the back of which was written “TONY,” above an Upper West Side street address.

“I met Anthony Bourdain at a dinner last night,” he said. “Really cool guy. He’s looking to hire someone to help him write a cookbook and I told him he should hire you. Write him a letter.”

From the book Care and Feeding: A Memoir by Laurie Woolever. Copyright © 2025 by Laurie Woolever. Published on March 11, 2025, by Ecco, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Reprinted by permission.

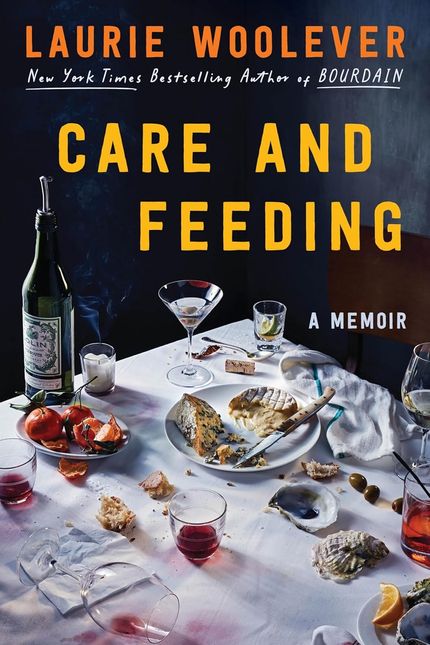

‘Care and Feeding: A Memoir,’ by Laurie Woolever

All Rights Reserved. Copyright , Central Coast Communications, Inc.