when you want, where you want.

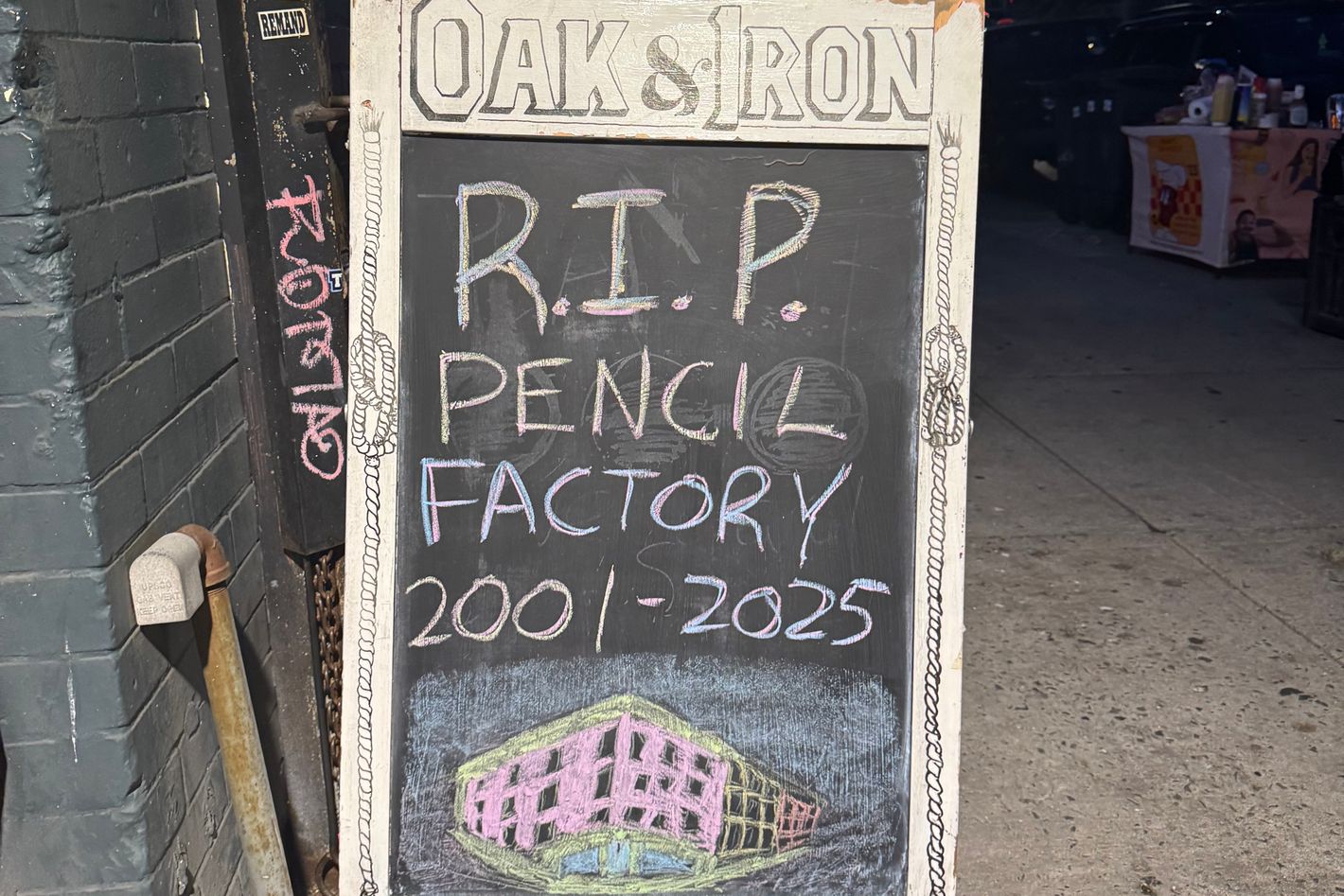

Good-bye to Pencil Factory

Photo: Charlotte Klein

Photo: Charlotte Klein

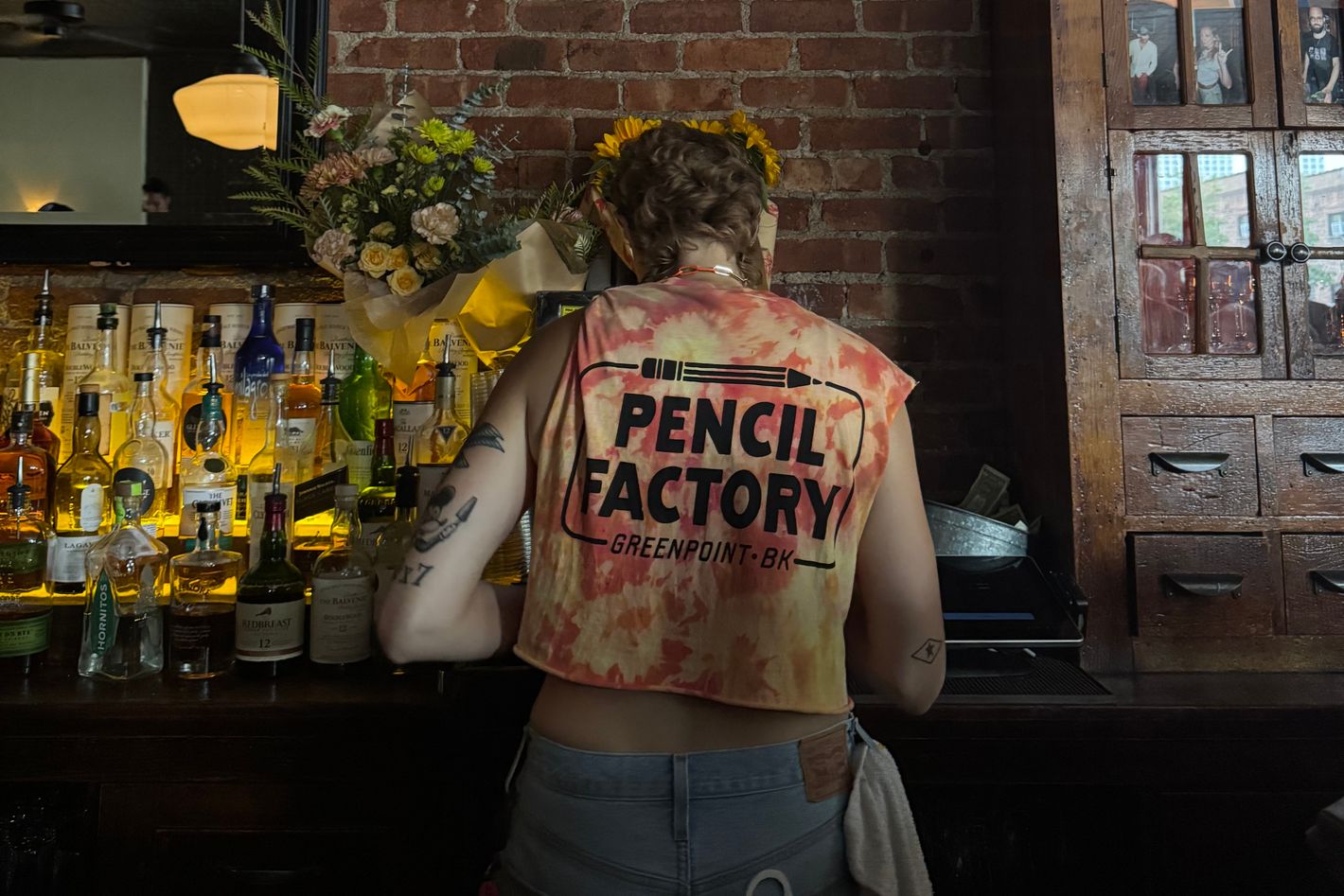

Yesterday was the bar’s last day. People had started lining up for any remaining merch before they’d even opened, and by 2 p.m. there was a crowd on the sidewalk. A few hours after that it’d turned into an ad hoc block party, with customers spilling into the streets, including one person in a pencil costume, and a man holding a cold beer in each hand while cradling a baby. A girl named Kate told me she’d met her husband, Tommy, at this bar, on his first night out in Greenpoint a few years back. “At the second stool in,” she said. “He brought his cute chocolate lab and I was like, I will not fall for this trick.” They have a baby of their own now named Brooklyn. She was there with a friend — they were wearing matching Pencil Factory hats — who remembered getting COVID here a few years ago, drinking in the long-gone outdoor dining shed during a snowstorm. Inside the muggy bar the menu had blue tape over most of the options, sold out from the rush of its last week, and a few bouquets that people had brought for the bartenders. Staffers wheeled in giant bags of ice. People danced in the windows. Someone brought pizza and their friends cheered.

Pencil Factory was a simple dive bar with surprisingly good wine and heavy pours. There were always dogs and often kids, for birthday parties or to trick-or-treat on Halloween. It sat on the corner of Greenpoint Avenue and Franklin Street that on a sunny day was bathed in light. At the first sign of spring people would flock to the small tables slanted on the sidewalk, sit in wicker chairs, and drink and watch the neighborhood, a mix of younger folk and families and, inevitably, that guy in Greenpoint who is always riding a bike with something like a TV or a trash can balancing on his head. Pencil didn’t serve food but encouraged everyone to bring their own, and we often did, wolfing down slices of Paulie Gee’s after too many margaritas.

Brian Taylor, Louise Favier, and Sean O’Rourke opened this place nearly a quarter-century ago. Taylor, who is now 62 and says he was “an attorney in another lifetime,” moved to Greenpoint in 1998, “back when you couldn’t get a cab here. It was a bit of a wasteland, so I spent the first years saying someone should open a bar in Greenpoint.” No one would, so he did, recruiting his then-romantic partner Favier, whom he’d met at the Ear Inn, and O’Rourke, to do it with him. “Brian loved bars. I had never met anyone who loves bars more,” Favier says. (Favier and Taylor have two kids together but aren’t romantically involved anymore.)

To start, Taylor made a list of ten places in the neighborhood where he might open, his favorite being an abandoned space once home to Miltonian Social Club, a haunt on the corner of Franklin Street for the longshoremen population during the neighborhood’s shipbuilding heyday. And then one day a handwritten “for sale” sign appeared outside. “I was living on Manhattan Avenue at the time, and I ran down at one in the morning and ripped the sign from the door,” says Favier, who feared that their friends at the Ear Inn would be tempted to take over the spot. “They’re dear friends of ours but not when you’re talking bars,” she recalls.

Pencil Factory opened in December 2001. “It was right after 9/11. New York felt like we’d just been rocked to our core,” says Favier, who remembers NYPD bagpipers marching down the street and into the bar on one of their first nights. “Because the ceilings are so low, it basically lifted the ceiling off; it was filled with sound,” she says. “People were in tears,” Taylor adds.

They got lots of things wrong at the start: Taylor and Favier had no experience owning a bar or working in one. “We would call our friends at other bars, saying, ‘How do you make an old-fashioned?’” Taylor says. “I got the space right,” he adds, “but behind the bar, we didn’t have a clue.” They made up for it by hiring experienced bartenders who immediately commanded the respect of customers, which in those days were mostly artists and musicians. (Back then the music would play from a five-disk CD changer, but they were so broke that they only had two CDs: one by Lucinda Williams, another by John Prine.)

Photo: Charlotte Klein

Photo: Charlotte Klein

Photo: Charlotte Klein

Photo: Charlotte Klein

They also remembered how hard it was to stay afloat at times, including when, six months after they opened, the city banned smoking indoors. “It emptied us,” says Taylor. One of the only other businesses in the area at the time was the Thai Cafe, and someone said they might draw more customers by selling Singha beer. “The next Monday, it was like, 12 cases, let’s go,” he says. “I think they’re still in the basement today.”

COVID was a turning point for the bar, which post-pandemic had a whole new staff and, the owners felt, renewed interest among locals. “On a Friday night or a Saturday night, we’d often be very quiet, because everyone had gone to Manhattan. After COVID, people were like, Screw it, we’re staying in the neighborhood,” Favier says. They started doing more events at the suggestion of their new manager, Mike, like jazz on Wednesdays, and changed the playlist, with more ABBA and Taylor Swift, to attract a younger crowd that’d dance in the windows until the bar closed at 4 a.m. “We were no longer the indie darling once we started playing the fun music,” says Taylor. It didn’t take long for TikTok to find out.

A frattier clientele moved in — especially on weekends, when they’d trek from Manhattan just for the dance party. “We lost a large percentage of artists and musicians,” says Taylor. “Certainly we have loved the business, but even just the comments on Reddit — someone said, ‘Oh, a bus from Milwaukee just unloaded in front of the Pencil Factory.’ They’re not wrong.”

When the bar opened in 2001, rent was $2,500 per month. This year, they were paying $13,000, and in the spring the landlord decided the new asking price would be $29,500 a month. Even if Pencil Factory’s owners could have paid the rent — which they couldn’t — they weren’t given the option to renew. “He wouldn’t give us specific reasons and just said that he was done, and then kind of went silent on us,” Taylor tells me. “If I were to guess, I think he’s just kind of over it.”

“The love of this neighborhood — it’s hard to leave,” says Favier, who moved to Seattle alongside Taylor a few years back. “We felt that magic the night we opened Pencil Factory — that sense that we were wanted here,” she says, “and the alchemy of the space, from the front door to when we bought the wood. We didn’t have time to let it season and then it shrank, and we were horrified, initially.” But the wooden planks became integral to the place, as did the original tin wall, and the wood cabinetry by the bar, and the old chairs and small tables that the bartenders started moving outside on weekends a few years back so that people could dance.

“I feel like we’ve really gone out on a high,” adds Favier, reflecting on the many iterations of the space, which in its last few weeks has seen people spilling out on the sidewalk no matter what day, a sight usually reserved for the weekend. “When it’s hard to pay the bills and it’s pretty quiet, I always loved walking in the door — I always loved the way it felt. Some bars work when they’re empty and some don’t. And this always worked great, but it is lovely to go out on such a celebratory period, rather than that feeling of like, Oh, we never really did it.”

Photo: Charlotte Klein

Photo: Charlotte Klein

Related

All Rights Reserved. Copyright , Central Coast Communications, Inc.